On a late summer day in 2015, Joey took me to the Yuba River. After a mile’s hike, we came to a sun-dappled pool deep enough to swim in. I stripped naked and baptized myself in the clear, honest water.

Afterward, we got hammered at a Nevada City tavern with Nisenan prostitutes from the rancheria.

I caught a ride to San Francisco. There were half a million people in Golden Gate Park, and I bumped right into my brother Alex. I had the shakes. He had a backpack full of beer.

I told him, “I don’t know if I can handle this right now.”

He said, “Sure you can.”

He found us a woodsy patch on the side of the park, and we leaned against tree trunks and opened beers. We had a view of the Banjo Stage where Justin Townes Earle and his band were about to play.

It took a few songs for me to drink myself healthy, but by the time Justin and the boys launched into the defiant folk tale “They Killed John Henry,” I was alive and locked in. “White Gardenias,” followed, drenched with pedal steel guitar, Justin’s phrasing inspired by Billie Holiday. The set’s highlight was the back to-back shots of two of Justin’s most strung-out ballads, “Christchurch Woman” and “Rogers Park.”

Five years later, combing the latest Coronavirus news reports, I learned that Justin Townes Earle had died. The last I’d heard about him was that he’d gotten clean and was living with his wife Jenn and their infant daughter Etta in southeast Portland, just a couple of miles from where I and Marilena and our cat Lucia shared an apartment in the shadow of Mount Tabor.

In the years preceding the pandemic, I’d grown too blind to read or write. With difficulty, I worked as a tutor and a pet sitter. Marilena bounced between jobs at a woodshop, a food truck, and the dish room of an Argentinian restaurant. I’d gotten my drinking more or less under control, but Marilena’s drinking was controlling her. Betrayals had been committed; trust had been corroded; after ten years of invincibility, our love was on the rocks.

When the lockdown hit, I stoked a cinder of hope. At the end of 2019, I’d undergone lens implant surgery in my right eye, and I could finally see the morning dew on camellia. With both of us collecting boosted unemployment checks, we had a surfeit of cash. Stuck at home with each other, we had the time to repair what was broken. I ordered a box of books from Powell’s and started writing a novel. I encouraged Marilena to make art and dry out.

Instead, she spent nine months in a near-permanent blackout, screwing open her first carton of wine by nine a.m. and chain-smoking cigarettes in bed with electrocuted eyes, emerging to dart across the street to the gas station for more wine. When I protested, she screamed that she was processing trauma. Perhaps she was, but the apartment was contaminated with her misery. I couldn’t write. Portland was shut down. I could only walk the paranoid city streets and the trails on Mount Tabor with my headphones on.

Although I’d never met him, I was lonely for Justin. On my walks, I played his albums in chronological order.

Justin was the son of famous songwriter—and famous addict—Steve Earle, but he was raised by his mother Carol in Nashville. By the time he was an early teenager, he was out of school, taking hard drugs, playing in bands, and writing songs.

His debut EP Yuma (2007) is a stark, startling statement. It opens with the sound of a music box, evocative of a broken childhood, and follows with nineteen minutes of Justin’s unaccompanied guitar and voice. The title track is his first great song, a conversational sketch of regret and self-destruction that maps the suicidal path Justin will travel to its inevitable end:

Looking back, I’d say it wasn’t so much the girl

as it was the booze and the dope

and the way he took the weight of the world up upon his shoulders

and let it wash the blue from his eyes as he grew colder

Quickly following Yuma, Justin’s first proper album, The Good Life (2008), fleshes out his songs with a cast of collaborators who add drums, piano, fiddle, bass, lap steel, and backing vocals. Justin’s omnivorous appetite for classic country, blues, ragtime, and Woody Guthrie folk is apparent as he shuffles from one style of American music to the next. Written from the perspective of a Confederate soldier, “Lone Tree Hill” is one of the most eerie and enduring songs in his catalogue. “Who am I to Say” reminds me of something Jackson Browne might’ve penned in the “Late for the Sky” era. “Turn out the Lights” follows “Yuma” as the next entry in Justin’s book of suicide poems:

Now I can feel the darkness fall

like the rain against the wind blows

And I can hear your memory

like a dream outside my window

If his first two albums sound like unearthed recordings of a mid-century train-hopping troubadour, Midnight at the Movies (2009) is the first release that feels contemporary. It announces a fully realized and singular voice in American music. Justin has learned everything he needs to know from his forebears, but he no longer sounds as if he’s imitating them.

The title track is a dreamy waltz about loneliness and longing in a theater. It possesses a teenage innocence, Justin yearning to replace the whiskey and powders of his own adolescence with the “candies and red hots” of a more wholesome American upbringing.

The most surprising moment on the record is his fantastic cover of the Replacements’ “Can’t Hardly Wait.” Featuring plaintive vocals and a mandolin line, Paul Westerberg’s classic seems to have been written for Justin. Later, he will replicate this magic trick with his take on Paul Simon’s “Graceland.”

The loveliest and most personal song on the record is “Mama’s Eyes,” in which Justin concedes that despite his fraught relationship with his father, he’s a sucker for the same modes of destruction:

I was a young man when

I first found the pleasure in the feel of sin

I went down the same road as my old man

Though suffused with melancholy, Midnight at the Movies is Justin’s most upbeat album. He seems hopeful. The more vulnerable songs— “Mama’s Eyes” and “Someday I’ll be Forgiven for this”—resolve with optimism (“I still see wrong from right”/” I’ll be Forgiven.”)

Harlem River Blues (2010), on the other hand, announces a renewed death drive with its opening couplet:

Lord I’m going downtown

to the Harlem River to drown

It’s a blast of rollicking gospel soul, complete with a drunken angel choir and an electrifying solo courtesy of Jason Isbell. Never before has suicidal ideation sounded so euphoric.

The last night on earth party vibes keep rolling with “One Last Night in Brooklyn” and “Move over Mama.” Half of the record swings, but on the back half, the high wears off, and Justin crashes to the floor. On “Learning to Cry,” a steel guitar weeps. On “Christchurch Woman,” the “rain keep comin’, but it ain’t enough to cover the pain.” And on “Rogers Park,” he’s all alone, the town is dead, and he has nowhere to be:

So take my heart and break it in

Send me back to the pines

I’m tired of lying awake at night

Feel like I’m running out of time

I was walking around the reservoir, listening to Harlem River Blues, and the piano figure that opens “Rogers Park” began, and something broke inside me. I had to sit and hold my face in my hands while I cried. I knew it was over.

I packed a bag and checked into Motel 6 on Powell Boulevard so I could spend a few days preparing the words I needed to say. Documentary about Timothy Leary’s lover on the television. Dark stain on the drawn curtain. I walked outside and smoked a cigarette on the concrete balcony, watching the firs shivering in the fuchsia sky, the owl eye moon refusing to blink.

I returned to the apartment and told her. She was ready, had a ride already on the way.

That same day, Justin’s cause of death was announced. It was like being told something I already knew.

I toasted depression bagels and washed my dishes in the bathtub because the kitchen sink was clogged, and I was too defeated to fix it. I broke my cigarettes in half, so they’d hit my lungs harder. Over and over, I watched Justin’s appearance on Letterman performing “Harlem River Blues” with Jason Isbell. Justin and Jason dressed to the nines and probably coked to the gills.

Steve Earle processed his grief the only way he knew how, by making music. He and his band the Dukes recorded ten Justin Townes Earle songs and one Steve Earle original at Electric Ladyland studio in New York. Steve said in an interview with the New York Times that it “wasn’t cathartic so much as it was therapeutic. I made the record because I needed to. It was the only way I knew to say goodbye.”

JT was released on January 4, 2021, just a few months after Justin’s death, on what would’ve been his thirty-ninth birthday. I expected it to be a painful listen: the fresh grief of a father paging through his child’s songbook.

Happily, the album is warm and full of love, a garden blooming from the country soil of mandolin, dobro, steel guitar, and fiddle. It draws mostly from Justin’s early records. “I Don’t Care” takes Yuma’s skeletal original and gives it a full bluegrass makeover. “Maria” is a rocker honeyed with mandolin. Finger-plucked guitar notes, Bonnie Whitmore’s cradling fiddle, and supportive backing vocals keep “Turn Out My Lights” from collapsing under the weight of the song’s sadness. Steve’s rasp haunts “Lone Pine Hill” like the ghost of the song’s regretful soldier, and he sounds tough as nails on “The Saint of Lost Causes,” selling lines like, “I’m the reason they say, ‘Watch your back,’” and “I must admit I kind of like the pain.”

Steve and the Dukes’ take on “Harlem River Blues” is rootsier than Justin’s, more San Antonio country than Memphis soul, fiddle replacing the organ of the original, upright bass skipping like a stone, pedal steel crying like a river. Steve’s vocals are more weathered than his son’s, but just as sprightly, even as he delivers Justin’s urgent note to, “Tell my father I tried.”

I met my brother at a Greek restaurant in Nashville, and together we walked toward the holy Ryman. Communicating with only a glance, we stopped short of the auditorium to duck into a bar for a couple of drinks. We’d both been working on getting sober, but we left that detail unmentioned. After all, we were headed to a funeral.

When we slid into our pew, the concert was already underway.

“Country shows start on time,” Alex noted.

The Dukes served as the house band while one by one a who’s who of Justin’s friends, mentors, collaborators, and tourmates came on stage to sing his songs.

Lily Hiatt delivered the first emotional gut punch of the evening, using her soprano notes to paint the lyrics of “White Gardenias.”

I hardly had time to catch my breath before Scotty Melton hit me with “Rogers Park,” a song I’ll now always associate with leaving Marilena.

Ben Nichols of Lucero provided some much-needed levity, ambling on stage with a drink in his hand to sing “Memphis in the Rain.” Nichols, a legend in Memphis, his voice a mixture of whiskey and gravel, was born to sing “Memphis in the Rain.” If I hadn’t known better, I would’ve thought it was Lucero’s best song.

After Nichols and his blue jeans and work boots, Jessica Lea Mayfield injected theatricality into the proceedings with her pink wig, pink dress, and white fur hand muff, singing “Learning to Cry” with the delicacy of a cherry blossom.

As he introduced Elizabeth Cook to the stage to sing “Someday I’ll be Forgiven for This,” Steve Earle mumbled, “I don’t know how I’m going to get through this.” Within moments, I was blinking back tears. The song had different resonance now that Justin was dead. A song about leaving one’s lover was now a song about leaving one’s life.

By way of announcing her to the stage, Steve declared: “The thing I’m most proud of in my life is that I know Emmylou Harris.” The worshipful Nashville crowd rose to its feet to greet its queen. Country music’s finest songbird rescued our spirits from the brink with a weightless performance of “One Last Night in Brooklyn.”

Before playing “Slippin’ and Slidin’,” Jason Isbell reminisced about the Letterman performance where he joined his friend on the talk show stage: “Justin bought me the suit I wore on that Letterman show. I didn’t have a suit. And he also bought me the suit I got married in. I didn’t have a suit for that either.”

Amanda Shires posed with Justin for the album cover of The Good Life. Wearing platform heels and a black cowboy hat, she brought her fiddle along for a soulful spin on that record’s “Ain’t Glad I’m Leaving.”

As we all knew it would, the show climaxed with a group singalong of “Harlem River Blues,” Steve Earle and Jason Isbell trading verses, Roscoe Ambel of the Dukes ripping through his guitar solo, Jason understating his, Emmylou sweetening the choir.

Then Steve Earle was left alone onstage for “Last Words,” the one original song he composed for JT, a clear-eyed lullaby that tells the story of the first time Steve held his baby son in his arms, and the last time he said goodbye on the phone.

Last thing I said was, “I love you”

and your last words to me were, “I love you, too.”

After the show, we hit up one of the honky tonks on Broadway. It was crowded; I pushed my way to the back. Bobby Bare Jr. was there nursing a Budweiser, sneaking out to the patio for a smoke. Ben Nichols sidewaysed by with a grin, ice glittering in his glass. It was Nashville.

We ran into Gina and Dylan, a couple we knew from high school in Hendersonville, NC. They had an Airbnb for the night, so we all went back there to drink PBR, listen to Drive-by Truckers, and gossip about our hometown.

Alex nudged me and said, “You’re cooler than you used to be.”

“I’ve always been cool,” I said, but I knew what he meant. I wasn’t strung out, and I wasn’t manic and unbearable. I listened to country music.

“What do you hear from Andries?” I asked Gina.

“Oh no,” she said. “You didn’t hear?”

***

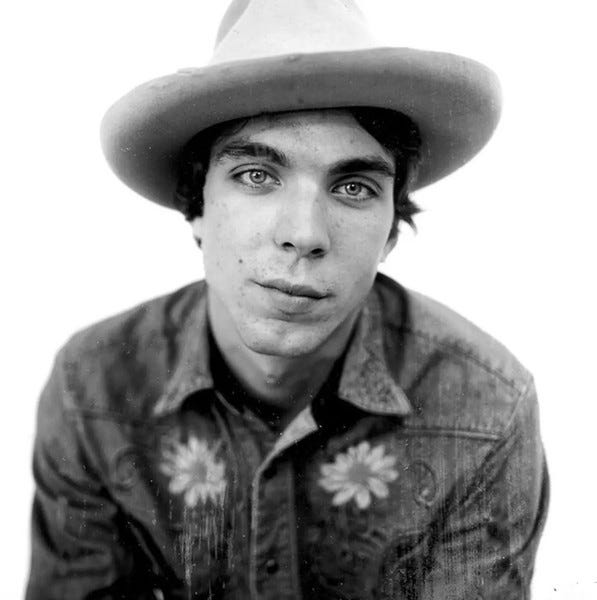

Andries Smith spent his first ten years in Pretoria, South Africa. Then his family moved to Hendersonville, NC. He was one year younger than me, almost exactly. I was born on February 22, 1986; Andries was born on February 24, 1987. I think that had something to do with how we were drawn to each other, got each other. I can see him clearly in my mind at Black Bear coffee shop on Main Street. That’s where we spent the most time together, after school, talking and playing chess. Andries was the smartest kid in town, but I could kick his ass at chess. I’m not saying that to brag. His smile was so endearing when he was frustrated. I was obsessed with frustrating him. He was so damn adorable. He looked a little like a Muppet or a Furby, with a head of tight curls, girlish lips, ironic eyes. I used to pinch his cheeks and tease him about how cute he was. It was entertaining; he took himself so seriously. He was the genius. He’d be the valedictorian. He was sardonic but not silly. He admired me. He wanted to discuss philosophy. But I just wanted to be silly with him, pinch his cheeks, love him, frustrate him, make him giggle. His accent was sexy. Girls melted. He lost his virginity before I did. I asked him what it was like, and he told me that sex wasn’t the best part about sex.

Andries’s older brother Ernst lived in the dorm room right next to mine. One time early in my first semester at college, I walked by Ernst’s room—his door was open—and saw him laughing at something on his computer screen. This was 2004. Chunky PC, pressboard desk, hard plastic chair.

“What’s so funny?”

He waved me in. I bent down to watch over his shoulder, and he restarted the video. The black and white clip was either security footage or made to look like security footage of a man sitting at a desk in a cubicle. Nothing’s happening. Then the man takes a gun out of his desk drawer, cocks it, puts it in his mouth, pulls the trigger, and blows his brains and blood all over the walls.

“WHAT THE FUCK,” I screamed, backpedaling out of the room.

I caught a ride to Chicago for the inaugural Pitchfork Music Festival and stayed with Andries. He was a freshman at the University of Chicago, living alone in a spartan apartment near the campus.

Andries and I took the train to Union Park then split ways to pursue our own respective fancies. I caught terrific sets by Mountain Goats and the Walkmen. It was a blazing hot July day, and I briefly passed out after dancing myself dizzy to Spank Rock. Some kind soul dragged my body to a shady patch of grass and placed a bottle of cold water by my side.

I rejoined Andries for the night’s main event. David Berman noted how bizarre it was for his band Silver Jews, unknown by the masses, to headline a festival in Chicago. It must be the critical acclaim, he mused. But it was something more akin to devotion.

Andries and I stood shoulder to shoulder and watched The Joos run through beloved country rock poems like “Random Rules,” “Slow Education,” and “Black and Brown Shoes.” As night blanketed Chicago, a breeze whispered through the park, and the moon appeared above the stage like a halo.

Back at his apartment, Andries had a plastic jug of vodka and a bowl of ripe lychees. All night, we ate lychees and shot vodka, and Andries couldn’t stop giggling. That’s how I’ll remember him—happy, with a lychee.