Mike didn’t look like a poet. He looked like a boy from Cumberland County, North Carolina, which he was. He was a sturdy man with a big, muddy beard. He wore an Atlanta Braves fitted cap, carpenter jeans, white tee, and Nikes. He looked like a weed dealer, which he was.

The first poem I saw him read was about taking glass hits of hash. We were at an open mic at a kava bar in Asheville. His voice trembled when he read. When he finished a page, he dropped it on the floor.

I’m careful with the hash

I’m not a rockstar

I don’t want to waste it

in a rush to huff it down

Not much makes it to the east coast

I take a small chunk

and put it on a needle

that I pressed through

a piece of cardboard

so it will sit up

like a little sculpture

I have a glass and a straw

I light the hash and blow it out

and put the glass over the needle like a globe

then I let it milk up the glass

then I tilt the glass back

and stick my straw into the opening and inhale

all the smoke

and then I almost pass out

and have an epiphany

about crystals and sacred geometry

then I forget it and do another hit

“Milk up the glass” struck me as a perfect way to describe the gathering hash smoke.

I was drinking a puddle of kava with a bite of pineapple and smoking a cigarette on the sidewalk when I spotted him standing alone in his fitted hat. I offered him a cigarette.

“Thanks bro, but I have asthma.”

I threw my own cigarette into the street. “Well, do you want to go to the Yacht Club and drink some whiskey?”

For a couple of months, every Wednesday, I’d go watch Mike read some poems at the kava bar, and then we’d drink whiskey at the Yacht Club and talk about poets we liked and girls we were trying to sleep with.

Then I moved away for a while, and we lost touch. A year later, I found him on Facebook and sent him a message.

I’ve been thinking about you.

Yeah I’ve been thinking about you too. What you been thinking?

That I’d like to eat that ass like a three-dollar blue plate spaghetti dinner. Nah just wondering if you’ve been writing and if you’d want to tip a couple with me sometime at the Wayside.

Yes man over a hundred poems this month …

He wasn’t exaggerating about the hundred poems. An insomniac, he’d write all night and post his poems to Tumblr. They were actually terrifying to read. He was untrained, but his writing was alive in a way I’d never encountered, breathing with nightmarish lust and longing.

We started hanging out every day. Smoking weed in the morning in his apartment, driving around town in his truck, dropping off weed to his customers, having drinks at Frazier’s (his side of town) or Wayside (my side of town), taking bottles of whiskey to my house to drink on the porch.

One summer evening, we were on the porch when a lightning storm dazzled the sky. I was annoyed because my lawn was overgrown and I’d meant to mow it that day, and now the rain would make it impossible.

Mike asked me what superpower I would choose if I could have any superpower.

“I wish I could mow lawns with the wink of an eye.”

“You’d be the hero of the suburbs then.”

I didn’t write poetry then. I wanted to write a novel. But spending time with Mike made me want to write poems. That night before going to sleep, I wrote a short poem and sent it to him on Facebook.

Hero of the Suburbs

Lightning isn’t in the sky but in our eyes, a chorale bolt

into the collective God-house of mirrors, infinite

reflection, you and me, you are me. Why is it that we agree

that you have a beard and sad eyes, every day of your life,

when you never stop moving up and down and side to side?

If I could have one superpower, it would be the ability to mow lawns

with a flash of my eye. I would cruise the neighborhood in a truck,

with my friend to keep me company, and I’d wink, and make every woman

happy to have a home, and a decent bearded man

In the morning, I awoke to a buzzing sound. I walked out on the porch, shielding my eyes from the sun. Mike was mowing my lawn.

That night, he sent me a poem on Facebook.

Hero of the Suburbs

fan blade razor wire

and the American front lawn

marriage counseling

through lawn maintenance

and solutions to drug addictions

weed whacking the knoll

I smiled as I pivoted the lawnmower

and a fantasy flashed across my eyes

the notion of the next great simile

I wanted to tell people what it was like

how a good woman was like a lawnmower

how they will always turn over for you the first yank of the cord

and how they don’t smoke in the tall grass

and this and that but I believed for the flash of a pivot

at the top of the side yard hill

that this would be the next great simile

because people love you when you tell them what it’s like

and in that instant of low-level thinking

during the perfect pivot back down the hill

the greatest simile I could think of

was how a good woman was like a good lawnmower

We started writing poems to each other every day; every poem was called “Hero of the Suburbs.” We went to the kava bar together and read them on Wednesdays, both of us wearing fitted hats. Before each poem, we deadpanned, “This one’s called “’Hero of the Suburbs.’”

We talked a lot about suicide. It’s a relief to be open with someone who understands and doesn’t judge or overreact. We were both prone to ideation. Mike heard voices that told him to hurt himself. I compulsively fantasized about blowing my brains out. He always told me that if I was going to shoot myself, I should put the bullet in my heart instead of my head. “Don’t ruin your beautiful face.”

He owned guns. He gave me a .22 once. We were sitting on his bed in the loft at his apartment. He showed me how to load it and took aim at an imaginary intruder.

“This won’t kill him, but it’ll slow him down.”

“Who do you think I’m most likely to shoot with that thing?”

He grimaced. “We’ll keep it here.”

He loved his sister, Alex. He was protective of her.

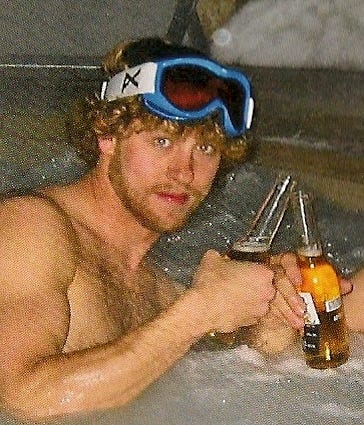

He had a heaven—Colorado. He’d gone snowboarding in the Rockies, and that’s where his heart stayed.

We were always hunting Benzos. We ate little green Klonipins like they were Tic Tacs. In 2012, everyone had a Klonipin scrip. You could trade cigarettes for them at the bar.

We coveted Xanax. Mike knew a recluse named Good John who lived in a trailer in the woods and sold Mike his entire Xanax prescription every month. Driving the backroads to Good John’s trailer, we felt like little boys on Christmas morning.

When we made afternoon weed drops, we listened to ASAP Rocky and The Lox. When we picked up Xanax, we listened to Lana Del Rey and Mazzy Star.

With winter came depression and paranoia about women, money, and drugs. I shiver remembering the whippets rattling in a box on the floor of his truck, the powder we snorted that smelled like the bag of caramel coffee it was packaged in, the crows in Mike’s eyes when he talked about Oxycontin.

Mike found a girlfriend and guarded her. By December we were barely speaking. We wrote a couple of heartsick Heroes at each other then he quit writing Heroes and resumed posting untitled poems to his Tumblr. I quit writing altogether.

But he called me late New Years Eve. He wanted to tell me that he’d gotten laid for the first time all year. Just before midnight—snuck it in.

He called me one afternoon in January and told me that he was playing with his gun. Then he hung up.

He called right back and said, “Don’t worry. Everything’s okay.”

Another night, he messaged me on Facebook.

Wish you were here. I can sleep when you’re here. I can trust you. I’ve been writing little four or five line poems.

Send me something.

a good dead end

gathers all the infinite

faces

of darkness

with nobody

noticing

there is a pendulum within the pendulum

and both have swung away

from me

this year

If you kill yourself, I’m going to steal all your poetry and pretend it’s mine.

That’s the ultimate compliment bro. Get a taxi over here, I’ll pay the man. We’ll crack this big bottle of red I’ve got. And smoke an ounce. And I’ve got Klonipins.

Hmm.

C’mon. I miss you.

So I took a taxi over, and we drank red wine, smoked blunts, snorted Klonipin until our nostrils were rimmed green, and listened to Frank Ocean. I slept on his couch.

On January 18th, he messaged me.

I’m having sort of a time man. Losing it. In pain.

On February 21st, my father died of a heart attack. I called Mike and told him, and we made plans to get drinks at Yacht Club the following day, my twenty-seventh birthday.

But Mike never showed up to Yacht Club.

On February 25th, he messaged me.

I bought a .45 Glock for $600

everything is peachy

I love you

I really love you

I wish life was better

On February 28th, I called him and asked if he would front me an ounce of weed that I could break into eighths and sell for a little cash.

He came through the back door, smiling, and tossed a freezer bag on the kitchen table. It was a quarter pound of high-grade weed.

“You don’t owe me anything,” he said. “This is a late birthday present. Just do me a favor—try to get three hundred a zip.”

I asked if he wanted to get a drink at Wayside, but he said he had customers coming by his apartment all afternoon.

“Do you want to hang out?” he asked.

We picked up a bottle of Jim Beam from the ABC store and drove to his apartment. Mike seemed clear, quietly radiant. I hadn’t seen him like that in a long time.

In a folding chair on the sidewalk outside his front door, I sipped whiskey and talked about my dad. Mike sailed his skateboard up and down the strip and listened. Every half hour or so, a customer came by, and Mike took him inside and sold him weed.

When it got cold, we went inside to smoke. There was a pistol on the coffee table.

“Is this your new Glock?”

I picked it up, impressed with its weight. I tapped it against my temple to see what it would feel like.

“Careful, Jeremy. It’s loaded. No safety on a Glock.”

I put the pistol down, between the towering glass bong and the dog-eared Collected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca.

On the drive back to my house, we joked about starting a book club and letting our girlfriends participate. We hugged and said goodbye.

That night, he texted me about the book club, suggesting we read Less Than Zero.

I told him we’d scare the girls off reading that psycho. He replied that Bret Easton Ellis was no more psychotic than the guy I liked (David Foster Wallace).

He texted once more that night, but I was already asleep and didn’t read it until the morning.

I took a taxi to his apartment and opened the unlocked door. The first thing I noticed was how chilly it was inside his apartment. The second thing I noticed was the blood stain on his green polyester armchair. The third thing I noticed was his sister Alex standing at the foot of the stairs.

“Oh, Jeremy,” she said.

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds had just released Push the Sky Away. Every night I stayed up late getting high and listening to the record.

And we breathe it in

There is no need to forgive

On March 16th, Marilena, Lexy, my brother Alex, and I drove to Nashville to see Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds at the Ryman. I was high on janky amphetamines. I hung back outside the doors and tried to put myself together. I was losing it. I staggered around with sad wild eyes until an eclipse of Bad Seeds fans floated around me like moths and comforted me and carried me inside the church.

When the preacher moaned, “Your funeral … my TRIAL,” his skull caught fire, and the fire consumed the Ryman and slammed into me like a wave, and my brain caught fire, and I fell on my knees.

***

Eleven years have passed since Mike’s suicide.

I live alone in an apartment complex in a peaceful neighborhood in Lexington. There’s a pool. There’s a dog park. There’s a dive bar across the way that has karaoke every night. Sometimes, early in the night, before it gets crowded, I’ll walk over there, buy one whiskey drink, sing “I’m No Stranger to the Rain,” and walk home.

I’ve been keeping a daily pain journal.

Radiating pain and stiffness in hips

Pain traveling up spine

Dull pain and stiffness in neck

Mild ache in fingers and toes

Medium depression

Some brain fog

Still getting work done

Walked to Kroger with difficulty

Temporary relief provided by hot shower and stretching

With foam roller

Then it got worse

Feelings of hopelessness

And thoughts of suicide

Wine and poetry. Get through the night.

All these years, I’ve carried Mike’s poems with me, a stack of them I copied from his Tumblr, pasted into a Word document, and printed out the day before his memorial at the kava bar. I’m grateful I did. His Tumblr vanished. His poetry would’ve vanished.

At the memorial, everyone wore fitted hats. One by one, the people who loved him, and the people who loved his poetry, came onstage and read Mike’s poems. Lexy sang, Marilena sang, all the strange angels of Asheville sang Mike’s song.

The poem I read that night was the last one he ever posted to Tumblr. He didn’t title it. (He hated titles.)

O the many odors of Michael

Everybody was right about him

And everybody was wrong

But that’s the way people look at

Art, anyways

But open your nostrils to a galaxy

Of infinite proportions and countless stars

Breathe deep the first breath when you enter my presence

I am there

The crumbs of ganja in my pockets sweet and tucked near

My asshole like a brown rose

My scrotum like a baby coconut

The sweat sticky cock laying curved on top

Through wiry pubic hairs rest a strange slick pink egg

The ancient air of a battleground hangs about

In the crevasse at the axis of my heavy arms in the stench of work

You can smell a flesh engine wet with the oils not of this earth

At my fingertips you can smell fine old broken in leather and chocolate

And my face smells like an old book

That nobody reads

And you were the first to fan through the pages

In a long while

But nuzzle deep in the center of my chest

This is where I smell like Michael the most

In my deep hard sternum, in the fir of a Norwegian pioneer

You can smell the Alaskan pines and the Colorado sunsets

And the cherished Christmas and the deep west calling to you

Smell the southern Utah red rock desert and the eastern Tennessee valleys

Smell the faint scent of a heart that seeps through my pores

It is the perfume of conviction

Be as close to me as you can against the membrane that separates

My fragile heart from the world

And smell me here

And know by the smell

I am here

And my heart

Beats and beats